This blog, “Animal rights activism is big business,” was first published by Hoard’s Dairyman here.

“They look like corporate, professional people wearing suits,” my friend exclaimed as I was talking to her about the Alliance’s work monitoring animal rights extremism. She used to live not far from People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals’ (PETA) headquarters in southern Virginia and couldn’t believe some of the methods they used to push their agenda.

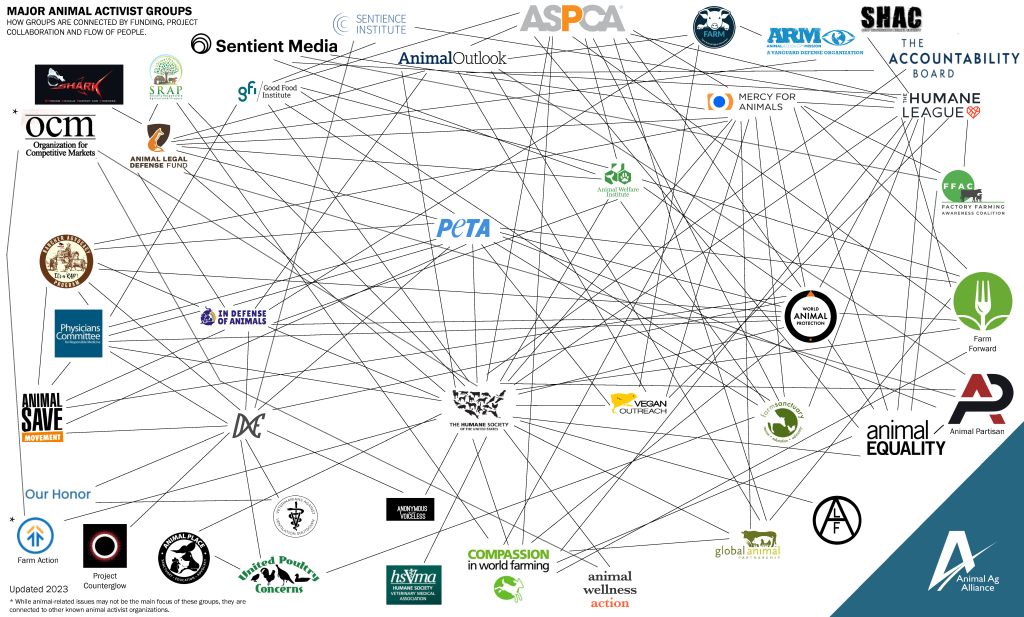

They all share connections

Members of well-known groups like the Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) and Mercy for Animals are often seen in suit and tie, perusing the halls of legislatures and shareholder boardrooms. They pose as seemingly moderate, level-headed nonprofits looking to improve the welfare of animals, but their true goals go much deeper than that with close-knit connections to much more extreme forms of activism. Most animal activist rights activist organizations – no matter how reasonable they attempt to appear publicly – share the same goal of eliminating or fundamentally altering animal agriculture. Some groups desire to take meat, milk, poultry, and eggs off our tables. Others call for mandates of practices that would make it impossible to meet the growing demand for animal protein. Oftentimes, they also share connections via funding, project collaboration, and flow of people. Each year, the Alliance updates our Animal Activist Groups Web to highlight these connections.

Make no mistake – animal rights activism is big business. Our Animal Activist Groups Web highlights some of the largest and most active groups but it does not include them all. The Alliance has profiled roughly 200 animal rights groups for our members on our Member Resource Center with a never-ending list of more that need to be researched. The few groups outlined on the map collectively bring in more than $800 million in income annually, up from $650 million in 2022.

Groups are primarily connected three ways

Flow of funds connect these organizations through sponsorships and grants that are awarded to one another. PETA, for example, is connected to outwardly extreme group Direct Action Everywhere (DXE) as a sponsor of DXE’s 2021 Animal Liberation Conference. One of DXE’s flagship tactics is the use of farm “rescues,” where activists will openly trespass onto a farm and steal an animal. With the support of PETA, activists did just that and stole four animals as part of the conference.

Project collaboration connections entail groups working collectively on an issue. This usually includes participation on the same coalition, signing onto joint letters, or co-hosting events. For instance, the Better Chicken Commitment coalition involves a number of organizations on the web working together to pressure suppliers, restaurants, retailers, and food service brands to adopt certain practices outlined in its “animal welfare” policy.

The final, and primary connector, of animal rights groups is the people who move from one organization to another. An example is the connection between HSUS and Animal Liberation Front (ALF). HSUS’ current senior director of the Stop Puppy Mills campaign is a former member of ALF, one of the most extreme groups we follow. The group has been identified as a “domestic terrorist” by the FBI, and their actions frequently include breaking and entering, releasing animals, and destroying property. While this is just one example, there are many more depicting seemingly sensible organizations like HSUS recruiting leadership with similar ideologies to the vandals involved in ALF.

No matter the tactics used or the organization’s public appearance, most animal activist groups are chasing the same goal and supporting each other as they do it – even if that includes supporting destruction, harassment, trespassing, and stealing. For more information about the Alliance’s work monitoring activism, visit www.animalagalliance.org/initiatives/monitoring-activism.

All posts are the opinion of the author and do not necessarily represent the view of the Animal Ag Alliance.